ONCE THE FOREMOST energy choice of the government, biogas has been relegated to the background, thanks to aggressive promotion of solar power. But biogas has advantages that solar doesn’t—it helps manage waste, costs less, and provides quicker return on investment. For some time, it seemed the government had given up on biogas. Even today, the National Biogas and Manure Management Programme focusses on biogas plants for households. So, does biogas have anything to offer on a larger scale?

Two IIM Bangalore alumni think it does. Mainak Chakraborty, 33, and Sreekrishna Sankar, 34, have set up GPS Renewables to sell a “biogas maker in boxes”. Set up in 2012, the Bengaluru-headquartered GPS Renewables’ flagship product is Biourja, a compact unit that can produce biogas on a large scale through a process of breaking down organic waste anaerobically, that is without using oxygen.

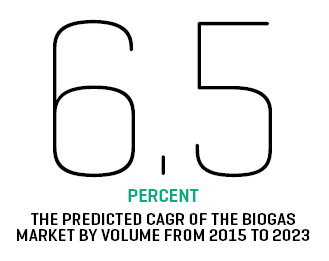

Although several small and medium-sized enterprises are involved in manufacturing biogas plants, data on the local industry is scant and not freely available. A report by Transparency Market Research predicts the market for biogas will grow 6.5% annually from 2015 to 2023 by volume. A search for “biogas plant” on the business-to-business marketplace Indiamart provides 707 product options.

What makes Biourja stand out is its size. Typical biogas and gobar (cow dung) gas units for family and household use range between 4 cubic metres and 5.5 cubic metres, according to a 2010 report by the Dutch development non-profit SNV, while industrial biogas plants can require several hundred square metres. In contrast, Biourja installations range from 12 sq. ft. to 80 sq. ft. “Mostly, biogas plants are very large and require a lot of space. In cities such as Mumbai, with its real estate costs, such solutions aren’t viable,” says Chakraborty.

For ITC Hotels, the company installed a biogas plant in 75 sq. ft., which took care of 30% of the monthly fuel needs for the five-star property’s kitchens and also helped manage its food waste.

GPS succeeded in reducing the size of its biogas unit by compressing its components, like the ‘digester’ where organic material is broken down, into smaller prefabricated units. The smaller size also helps clients save time and money in installation. This factor is critical because as the Transparency Market Research report points out, “the only factor restraining the growth of the global biogas market is the huge installation cost”.

Chakraborty agrees. “Usually, biogas plants need a lot of civil engineering work for installation,” he says. “But our plants are pre-fabricated at our facility in Bengaluru. Installation hardly needs any civil engineering.”

There’s more that makes Biourja innovative. GPS makes sure the plants don’t suffer downtime because of mechanical glitches. Using the Internet of Things, the technology behind connected devices, GPS constantly tracks the performance of each of its plants remotely. Data from the plant, transmitted to the Bengaluru hub, shows how efficiently it is breaking down organic matter and producing biogas. “Each Biourja plant has a SIM card, which gets inputs from sensors embedded in the plant. In addition, we have a proprietary health checker,” says Chakraborty. He declines to share exactly what is measured, calling the parameters “our secret sauce”.

GPS analyses the data to identify any potential red flags and fixes the flaws before they lead to plant failure. Since the type of organic waste keeps changing—from livestock waste to agricultural refuse to food waste—plants need to be adjusted constantly. “If [a problem is] diagnosed and treated early, we can prevent breakdowns,” says Chakraborty. Physical monitoring is taxing, which is why plants often stop working and are abandoned.

BIOURJA IS A RESULT OF INNOVATION across engineering disciplines—mechanical to electronics to chemical engineering—made possible with inputs from a posse of experts in these fields. Sreekrishna had been part of the Free Software Foundation, which had given him a good exposure to using technology for solving social problems. Chakraborty had worked with a telecom product startup in Bengaluru, where he had gained experience in design. However, the two felt their prototyping experience was not sufficient. So, they got in touch with Praveen S, Sreekrishna’s senior from engineering college. Praveen, who has a mechanical engineering background, is an innovator who keeps tinkering with different products in his garage for the joy of invention. “It is tough to find such hands-on engineers in India,” says Chakraborty. “Once we had Praveen on board, we were good to go.” Praveen now heads engineering at GPS and is the company’s chief operating officer.

They travelled across India to talk to potential customers, understanding the pain points, the shortcomings of existing products, and watching biogas plants in action. Based on what they learnt, they drew up a design blueprint and pooled Rs 18 lakh from their personal savings to build the first prototype. They ran the prototype for two years, and kept fine-tuning the design, till they bagged their first order from a nonprofit, Akshaya Patra. “We worked on the Akshaya Patra plant for a year before going for full-scale commercialisation,” says Chakraborty.

For someone in a capital-intensive business, Chakraborty has been surprisingly laidback about capital. Until the company’s recent foray into the U.S. market, the company had raised just a seed round of about $40,000 (Rs 25.3 lakh) from incubator Venture Factory in 2012.

Chakraborty says he has been running comfortably on sales of his Biourja plants. “We’ve got our margins there, and we reinvest that in R&D. We are unit profitable and we’ve only raised project finance for individual projects from high-net-worth individuals.” He refuses to share details about the price of a Biourja unit or figures regarding the business.

ALTHOUGH A YOUNG COMPANY, GPS has found high-profile takers for Biourja. These include IT giant Infosys, which has installed a unit at its Hyderabad campus; BITS Pilani in Hyderabad; Manipal University; Akshaya Patra; and the Art of Living.

BITS Pilani’s Hyderabad campus is the site of a unique experiment, with Biourja doubling as a waste management system and research facility. P. Sankar Ganesh, who teaches at the university’s department of biological sciences and is a member of international professional bodies on waste reduction, picked Biourja in 2014 to help deal with nearly 400 kg of organic food waste from the campus mess. But the plant is also playing a role at a different level—it is a subject of research for the university. “Around 10 students have completed thesis projects on Biourja,” says Ganesh. “We work with GPS to conduct research on what other kinds of feedstock can be used in the plant, apart from food waste.” So far, they’ve experimented with faecal sludge, the excrement stored in septic tanks, and agricultural waste.

An expert in anaerobic digestive biogas plants, Ganesh says the plant’s efficiency is far more than most conventional designs. “The plant makes more biogas per kilogram of waste, and it has more methane per unit of biogas produced.” Higher methane content means more energy from the biogas. Besides, the plant takes up just 12 cubic metres, and costs Rs 20 lakh.

GPS has also found a partner in the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, which has set up notable institutions such as the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, and the Tata Memorial Hospital. Along with the trust, GPS has launched a pilot project to source and process organic waste in areas under the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai. The L, K, and M wards, which cover Kurla, Powai, and other eastern suburbs, have been picked for the first stage. A plant will have the capacity to process 20 tonnes of waste a day. The biogas produced will be sold to local industries to substitute their energy needs from conventional sources. Kurla is home to many of Mumbai’s automobile and automotive parts factories, which are large energy consumers.

While working on the project with the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, GPS realised that in India energy generation is the business to go after, rather than waste management. “India doesn’t have a strict policy of waste disposal and segregation,” says Chakraborty. “Once it reaches the dumping grounds of Mumbai, it is impossible to separate organic waste, not to mention inhuman.” Instead, the company has set up “captive projects” with the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai to segregate and process organic waste right at the source. It can then work on getting the right feedstock to the plant. The Mumbai project will be more focussed on substituting energy needs of target industry clients, with waste management a by-product.

GPS has 35 clients in 12 states whose plants individually produce between 20 tonnes and 100 tonnes of waste per day on average. Apart from India, GPS has set up plants for Bangladesh’s largest poultry farm, Kazi Farms. The company’s next stop is the U.S., where unlike India, it aims to win clients who need waste-management solutions.

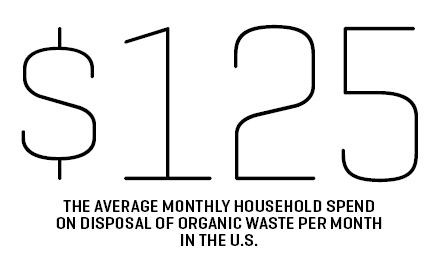

In the U.S. and other developed markets, organic waste disposal is a huge expense. “People spend $100 to $150 per month on disposing waste,” says Chakraborty.

It’s a vast market for Biourja, and Chakraborty has been making frequent trips to the U.S., conducting talks with city councils (American counterparts of municipal corporations) and with the authorities of New York city, and the states of New York and New Jersey.

Patrick Fraioli, a partner in a law firm based in Beverley Hills, California, is helping GPS raise money and get deals in the U.S. Fraioli met Chakraborty about nine months ago and agreed to partner the company as well as invest in it. “A group of investors have put several thousand dollars in the company,” he said. “We’re seeking more money in stages. We will look for that once the first demonstration unit is here in California.”

Fraioli helped GPS get its first client in Palm Springs, California, where says an upcoming real estate expansion will boost demand for waste management solutions. “Regulations in California are also taking hold, encouraging the use of biogas plants,” says Fraioli. California’s Self-Generation Incentive Program gives subsidies to residents who instal systems that use new and emerging energy sources, including waste-to-energy ones such as biogas plants.

From July, the first Biourja plant will go live in California (Chakraborty declines to name the client, citing legal agreements) and will soon be setting up a factory in the U.S. to manufacture the prefabricated plants for American clients.

THE MOVE TOWARDS CUTTING greenhouse gas emissions has given biogas an opportunity to stage a comeback. In the 1960s, the Indian government, along with the Khadi and Village Industries Commission, set up thousands of biogas and gobar gas plants, adapting the design for rural household use. But many of these plants were steadily abandoned as local authorities failed to maintain and repair them.

The next wave came with the National Programme for Biogas Development, which was introduced in 1981 with the Sixth Five Year Plan. This programme was renamed the National Biogas and Manure Management Programme in 2007 under the Ministry of Renewable Energy. Since then, its focus has largely been rural.

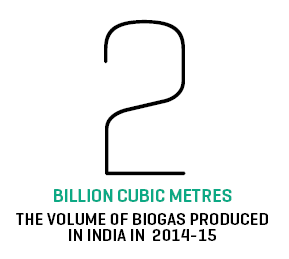

In May this year, the central government announced the setting up of 10,000 new biogas plants in the country. However, only 42.7% of the plants announced the previous year were installed till the end of FY16. In a reply to questions raised in the Lok Sabha last year, Piyush Goyal minister of state for power, coal, new and renewable energy said that nearly 2 billion cubic metres of biogas was produced in 2014-15. According to data journalism blog Factly, this is equivalent to about 5% of India’s annual LPG consumption.

While the government continues its focus on rural installations, companies such as GPS are free to focus on urban clients. The challenge lies in convincing these clients to pay for waste management—a goal that still figures low on corporate priorities.