WHEN ANIL RAI GUPTA took over as chairman of Havells India in 2014 following his father Qimat Rai Gupta’s demise, the consumer electronics major was largely into switchgear, fans and cable manufacturing. Anil, an MBA from Wake Forest University in the U.S., expanded the business into solar products and home automation, acquired the Lloyd brand in 2017, and entered air-conditioners, LED TV and washing machine businesses — making Havells a complete consumer durables firm. When the pandemic struck, he focussed on consolidation and financial discipline.

The result: Havells India posted two back-to-back years of over ₹1,000 crore in net profit. Net sales increased 68% to ₹16,910 crore in five years, while profit went up 36% to ₹1,072 crore. Gupta is now considering foraying into refrigerator manufacturing as it will broaden the Lloyd portfolio to take on the likes of global giants LG and Samsung.

Fresh from the effects of a Covid-induced slowdown, India Inc. is witnessing a new hunger to dominate in companies that already have a formidable presence in their respective sectors, and have devised expansion, consolidation and financial strategies.

The big, therefore, are becoming bigger. Some are making a mark in global sweepstakes, by featuring in the worldwide pecking order. For instance, after the merger of HDFC Bank and HDFC, the merged HDFC Bank will become the world’s seventh-largest lender.

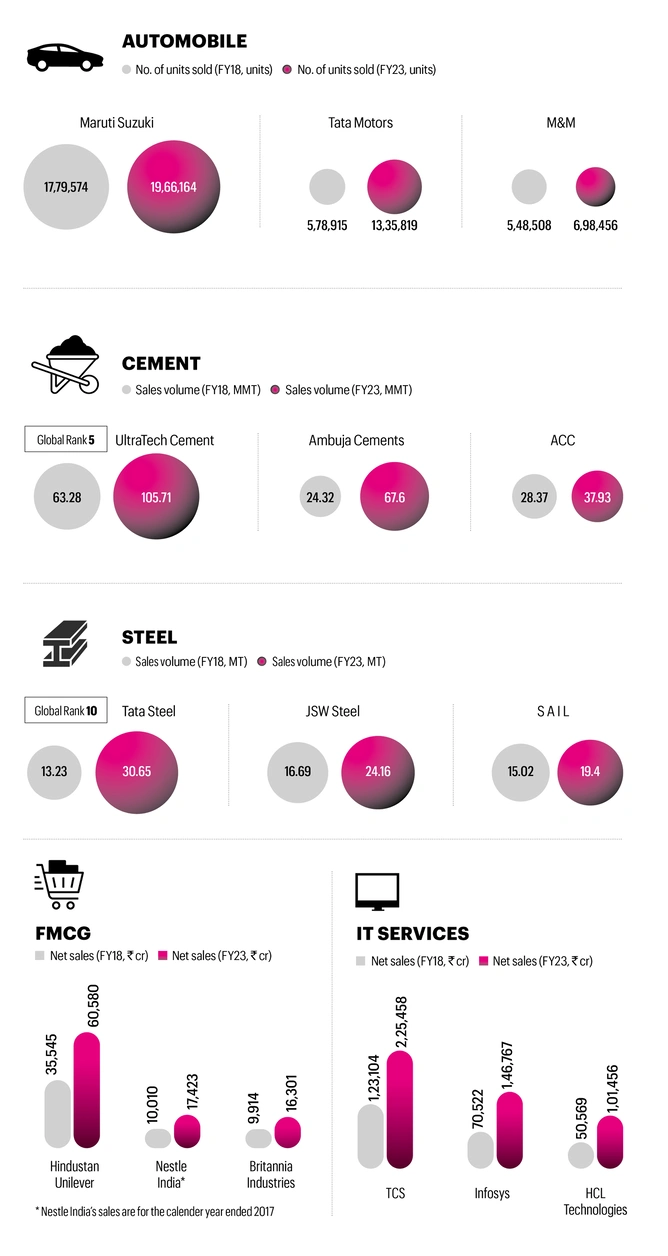

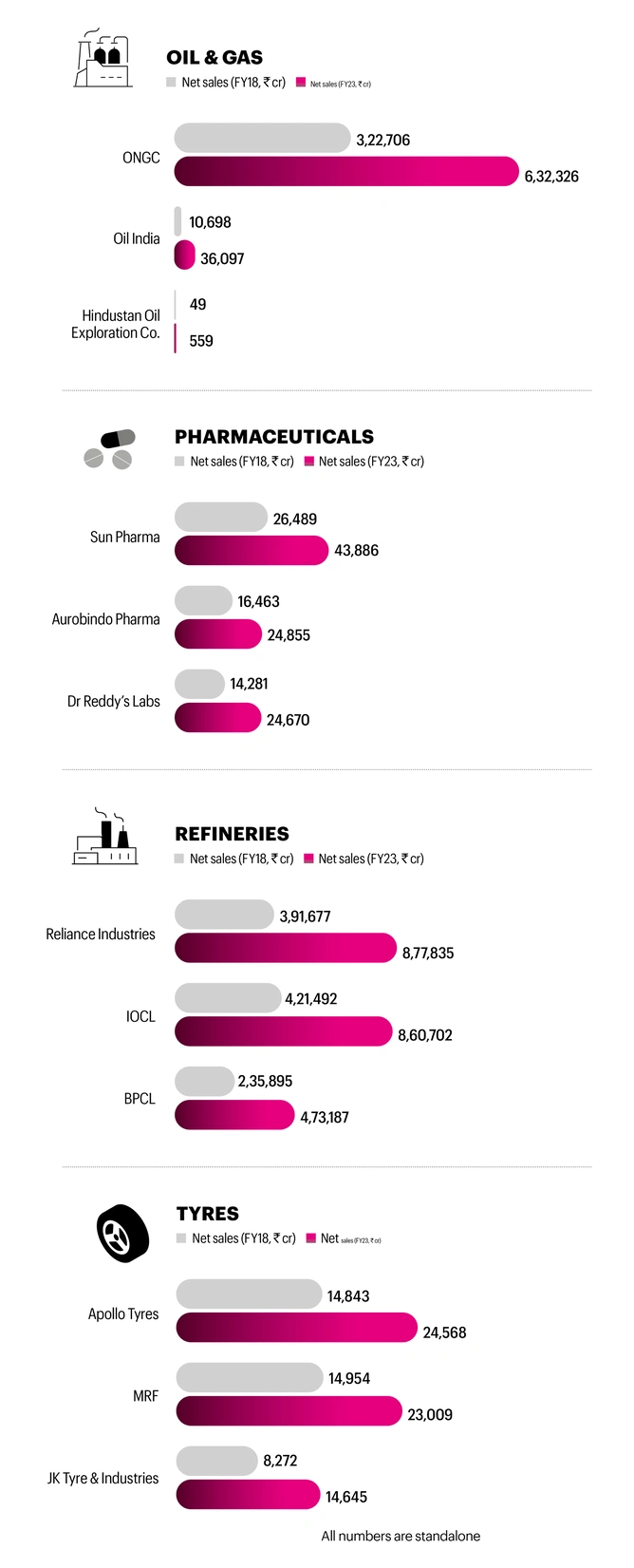

Hero Honda is the largest two-wheeler manufacturer by volume. Bharti Airtel is the second-largest telecom company after China Mobile on the basis of its subscriber base in India and Africa, while Reliance Jio is third in the global list. Reliance Industries has the world’s largest refining capacity in a single location. UltraTech is now the fifth-largest cement producer. Tata Steel is the 10th largest and JSW Steel 15th in the global list. Reliance Retail has consolidated its position in the last four-five years as the largest retailer in India, and the only one to feature among the top 100 globally. Hindustan Unilever contributes the highest sales volume in Unilever, one of the world’s leading FMCG companies. TCS and Infosys also rank among the top IT services companies, globally.

The rise in size and scale is on the back of a strong financial performance. Nifty 500 companies clocked a record profit of ₹11.1 lakh crore in FY23, an 8.8% increase year-on-year. The growth of the banking sector has substantially aided the rise.

“The exposure of Indian companies in the global market in the last two decades helped them to dream big and challenge the best across the world,” says Deven Choksey, MD, KR Choksey Shares and Securities. “Consumption is rising in the country. Leaders across sectors will have to ramp up production. Indian companies are adhering to sustainability and innovating on their own. It’s a welcome change,” he says.

Not An Easy Ride

The journey hasn’t been easy though. Among tyre makers, Apollo and MRF, which feature in the global pecking order, have built their businesses brick by brick. Both companies fared well in the last decade despite cost-reduction pressures and spike in rubber prices and import duties. They focused on core competencies and expanded in potential markets, besides finding new export opportunities, according to analysts. Apollo’s revenues grew at a CAGR of 10.6% in the last five years, while net profit jumped 132% in three years. MRF posted a revenue CAGR growth of 9% despite the dips during lockdowns, though profit dipped 46%.

“Last year’s problem of semiconductor shortage has more or less disappeared. The production level of automobile industries reflected this. Electric vehicle is now the new trend playing out,” says K.M. Mammen, chairman and MD, MRF, in the company’s latest annual report.

The biggies continued their domination in the auto industry, with Tata Motors leading the turnaround brigade. The Tata Group firm, struggling with losses, cashed in on the emerging EV manufacturing business with the launch of back-to-back products. It is now the largest player in the segment while Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra are yet to finalise their EV transition.

Tata Motors (India) sold 5,40,965 passenger vehicles in FY23, including 50,043 EVs, against 2,10,500 units in FY19. Net sales stood at ₹3,45,967 crore in FY23, compared with ₹3,01,938 crore in FY22. The company, however, made a remarkable turnaround with a net profit of ₹2,414 crore in FY23. It had posted a loss of ₹28,933 crore in FY19. In fact, in the next three financial years (FY20-22), it posted losses of over ₹10,000 crore each year.

EVs will be Tata Motors’ focus in the years to come, says N. Chandrasekaran, chairman, Tata Sons. It already has three EV models — Tiago, Tigor and Nexon, and plans to launch four more by 2025, Chandrasekaran said at the company’s recent annual general meeting.

Tata Motors’ EV arm recently signed a licensing pact to source electrified architecture from Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) for the development of its Avinya car series. According to analysts, the company’s quick decision making has helped it get the extra advantage in the EV market.

India’s largest car maker Maruti Suzuki India’s production accounts for around 60% of the global production for Suzuki Motor Corp. (SMC). Maruti garnered its highest-ever total sales at 19,66,164 units in FY23 despite the semiconductor shortage, which severely affected the global automobile industry. Its previous best of 18,62,449 units was in FY19.

Steel is another sector which has seen biggies adding heft to their operations and bottomlines. About 20 years ago, Indian steelmakers were miniscule compared to their Chinese, Japanese and European counterparts. Though Tata Steel failed in its ambition of becoming an European giant, it created capacities in India through greenfield projects and acquisitions — it currently has 20 million tonne (MT) of domestic capacity. The largest steelmaker in the domestic market, JSW Steel also spent heavily to build about 27MT capacity in the country.

Tata Steel’s consolidated net sales went up 74% to ₹2,43,353 crore during FY21-23, while JSW Steel reported a 126% increase to ₹1,65,960 crore during the period. The Tata Group firm made a slew of acquisitions, including Bhushan Steel, the steel business of Usha Martin, and Neelachal Ispat Nigam in the last three-four years to increase capacity. JSW Steel, on the other hand, bought Bhushan Power and Steel and Monnet Ispat.

JSW Steel, which once faced loan default in the 90s, is now cautious of its liabilities while deploying capital for expansion. The company, which had a debt of ₹66,797 crore in June, plans to spend ₹37,300 crore to increase its capacity to 37MT by March 2025. Tata Steel, meanwhile, is looking to double its domestic capacity to 40MT by 2030. Lakshmi Mittal-led ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steelmaker, and its joint venture partner Nippon Steel are also investing to expand steelmaking capacity in Hazira to 15MT from 9MT. Analysts say consistent investment is crucial to maintaining the lead in the sector.

In cement, UltraTech has lined up new investments to establish its foothold. The Aditya Birla Group Company plans to invest ₹13,000 crore in the third phase of its capacity expansion of 21.9MT. The company, which currently has about 137.85MT, is eyeing 200 MTPA, chairman Kumar Mangalam Birla said at the company’s AGM in August.

UltraTech, which invested over ₹50,000 crore in the last seven years, has seen a 50.1% increase in net sales during FY21-23. Net profit rose 12.7% during the period. But the cement landscape has now changed, thanks to Adani Group’s acquisition of Holcim’s stake in ACC and Ambuja Cements for over ₹51,000 crore in 2022. The group is now planning to double capacity to 140MT by 2028. Incidentally, Switzerland-based Holcim has been UntraTech’s biggest rival.

“The top players in every segment have been through economic turbulence and sectoral dips. They know the market deeply and invest in innovations to stay ahead of the curve. For them, adding size and scale is a natural progression,” says Anuj Agarwal, chief economist at asset management firm TruBoard Partners.

Consumer Takes Centre Stage

As Indian businesses take a leap, consumers have a key role to play in their growth strategy as well. Little wonder that cash-rich conglomerates are rushing to woo consumers with new sets of businesses. While India’s biggest private sector company, Mukesh Ambani-led RIL, has forayed into telecom and financial services and is looking to enter solar energy and battery storage, Tata Group has built FMCG, airline and e-commerce with fresh capital and acquisitions. The Aditya Birla Group is focusing on paints, expanding across the country.

Expansion seems to be the main route to growth for most companies, especially consumer-centric businesses such as fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), retail, telecom and pharma. New entrants are fuelling competition in these segments. Legacy firms are fighting back through expansion, better capital management and acquisitions. For instance, Bharti Airtel has maintained its leadership with a customer base of around 540 million across 16 countries. However, it is second to Reliance Jio in India, which had 417 million customers in August, compared to Airtel’s 376 million.

The Sunil Mittal-led company had closed FY19 with a 62.7% year-on-year drop in consolidated net profit at ₹410 crore, dented by a continuing tariff war with Reliance Jio, which launched in 2016. But it fought back with infrastructure upgrade, and faster 4G, 5G launches. Profit also picked as the company improved its performance on the business front. Sales, too, went up 59% to ₹1,39,145 crore between FY21 and FY23.

The retail sector has also seen a complete makeover with the fall of Future Retail (which operated Big Bazaar) and rise of Reliance Retail. In the last seven-eight years, Ambani’s retail chain has increased its geographical presence to 18,650 stores in September, compared with 3,837 stores in March 2018. The retail giant posted a profit of ₹9,181 crore on a revenue of ₹2,60,364 crore in FY23.

The entry of cash-rich conglomerates in new sectors disrupts markets. The panic was seen when Aditya Birla Group announced its ₹10,000-crore investment plan for the paint business. But market leader Asian Paints, which is also one of the top 10 paint makers globally, remained undeterred. The company, which forayed into modular kitchens and bathroom fittings via acquisitions about 10 years ago, entered the home improvement and decor segment. It has taken the product innovation and competitive pricing route to protect its turf.

The flipside of the rise of big companies is that the respective sectors will find it difficult to breed new companies which have low capital. The big ones will quickly adopt the best practices and products of the new entrants and apply/distribute them across markets. However, ventures with breakthrough ideas will always remain a challenge for the giants.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required field are marked*